The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States. It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue. And this will be thought no inconsiderable recommendation of the Constitution, by those who are able to estimate the share which the executive in every government must necessarily have in its good or ill administration. Though we cannot acquiesce in the political heresy of the poet who says: For forms of government let fools contest That which is best administered is best,'' yet we may safely pronounce, that the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.

The Federal Convention sent the proposed Constitution to the Confederation Congress, which at the end of September 1787 submitted it to the states for ratification. Immediately, the Constitution became the target of many articles and public letters written by opponents of the Constitution. For instance, the important Anti-Federalist authors "Cato" and "Brutus" debuted in New York papers on September 27 and October 18, 1787, respectively.[7] Hamilton decided to launch a measured and extensive defense and explanation of the proposed Constitution as a response to the opponents of ratification, addressing the people of the state of New York. He wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."[8]

Hamilton recruited collaborators for the project. He enlisted John Jay, who after four strong essays (Federalist Nos. 2, 3, 4, and 5), fell ill and contributed only one more essay, Federalist No. 64, to the series; though he wrote a pamphlet in the spring of 1788, An Address to the People of the State of New-York, that made his distilled case for the Constitution (Hamilton cited it approvingly in Federalist No. 85). James Madison, present in New York as a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress, was recruited by Hamilton and Jay, and became Hamilton's major collaborator. Gouverneur Morris and William Duer were also apparently considered; Morris turned down the invitation, and Hamilton rejected three essays written by Duer.[9] Duer later wrote in support of the three Federalist authors under the name "Philo-Publius," or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written. While many other pieces representing both sides of the constitutional debate were written under Roman names, Albert Furtwangler contends that "'Publius' was a cut above 'Caesar' or 'Brutus' or even 'Cato.' Publius Valerius was not a late defender of the republic but one of its founders. His more famous name, Publicola, meant 'friend of the people.'"[4] It was not the first time Hamilton had used this pseudonym: in 1778, he had applied it to three letters attacking Samuel Chase.

[edit] Publication

The Federalist Papers appeared in three New York newspapers: the Independent Journal, the New-York Packet, and the Daily Advertiser, beginning on October 27, 1787. Between them, Hamilton, Madison and Jay kept up a rapid pace, with at times three or four new essays by Publius appearing in the papers in a week. Garry Wills observes that the pace of production "overwhelmed" any possible response: "Who, given ample time could have answered such a battery of arguments? And no time was given."[10] Hamilton also encouraged the reprinting of the essay in newspapers outside New York state, and indeed they were published in several other states where the ratification debate was taking place. However, they were only irregularly published outside New York, and in other parts of the country they were often overshadowed by local writers.[11]

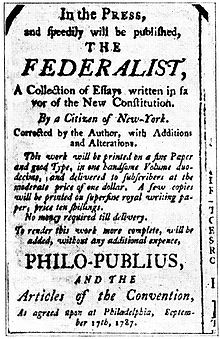

The high demand for the essays led to their publication in a more permanent form. On January 1, 1788, the New York publishing firm J. & A. McLean announced that they would publish the first thirty-six essays as a bound volume; that volume was released on March 2 and was titled The Federalist. New essays continued to appear in the newspapers; Federalist No. 77 was the last number to appear first in that form, on April 2. A second bound volume containing the last forty-nine essays was released on May 28. The remaining eight papers were later published in the newspapers as well.[12]

A number of later publications are worth noting. A 1792 French edition ended the collective anonymity of Publius, announcing that the work had been written by "MM Hamilton, Maddisson E Gay," citizens of the State of New York. In 1802, George Hopkins published an American edition that similarly named the authors. Hopkins wished as well that "the name of the writer should be prefixed to each number," but at this point Hamilton insisted that this was not to be, and the division of the essays between the three authors remained a secret.[13]

The first publication to divide the papers in such a way was an 1810 edition that used a list left by Hamilton to associate the authors with their numbers; this edition appeared as two volumes of the compiled "Works of Hamilton." In 1818, Jacob Gideon published a new edition with a new listing of authors, based on a list provided by Madison. The difference between Hamilton's list and Madison's formed the basis for a dispute over the authorship of a dozen of the essays.[14]

Both Hopkins's and Gideon's editions incorporated significant edits to the text of the papers themselves, generally with the approval of the authors. In 1863, Henry Dawson published an edition containing the original text of the papers, arguing that they should be preserved as they were written in that particular historical moment, not as edited by the authors years later.[15]

Modern scholars generally use the text prepared by Jacob E. Cooke for his 1961 edition of The Federalist; this edition used the newspaper texts for essays nos. 1-76 and the McLean edition for essays nos. 77-85.[16]

[edit] Disputed essays

The authorship of seventy-three of the Federalist essays is fairly certain. Twelve of these essays are disputed over by some scholars, though the modern consensus is that Madison wrote essays Nos. 49-58, with Nos. 18-20 being products of a collaboration between him and Hamilton; No. 64 was by John Jay. Some newer evidence suggests James Madison as the author. The first open designation of which essay belonged to whom was provided by Hamilton, who in the days before his ultimately fatal gun duel with Aaron Burr provided his lawyer with a list detailing the author of each number. This list credited Hamilton with a full sixty-three of the essays (three of those being jointly written with Madison), almost three quarters of the whole, and was used as the basis for an 1810 printing that was the first to make specific attribution for the essays.[17]

Madison did not immediately dispute Hamilton's list, but provided his own list for the 1818 Gideon edition of The Federalist. Madison claimed twenty-nine numbers for himself, and he suggested that the difference between the two lists was "owing doubtless to the hurry in which [Hamilton's] memorandum was made out." A known error in Hamilton's list—Hamilton incorrectly ascribed No. 54 to John Jay, when in fact Jay wrote No. 64—has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion.[18]

Statistical analysis has been undertaken on several occasions to try to decide the authorship question based on word frequencies and writing styles. Nearly all of the statistical studies show that the disputed papers were written by Madison.[19][20]

[edit] Influence on the ratification debates

The Federalist was written to support the ratification of the Constitution, specifically in New York. Whether they succeeded in this mission is questionable. Separate ratification proceedings took place in each state, and the essays were not reliably reprinted outside of New York; furthermore, by the time the series was well underway, a number of important states had already ratified it, for instance Pennsylvania on December 12. New York held out until July 26; certainly The Federalist was more important there than anywhere else, but Furtwangler argues that it "could hardly rival other major forces in the ratification contests"--specifically, these forces included the personal influence of well-known Federalists, for instance Hamilton and Jay, and Anti-Federalists, including Governor George Clinton.[21] Further, by the time New York came to a vote, ten states had already ratified the Constitution and it had thus already passed — only nine states had to ratify it for the new government to be established among them; the ratification by Virginia, the tenth state, placed pressure on New York to ratify. In light of that, Furtwangler observes, "New York's refusal would make that state an odd outsider."[22]

As for Virginia, which only ratified the Constitution at its convention on June 25, Hamilton writes in a letter to Madison that the collected edition of The Federalist had been sent to Virginia; Furtwangler presumes that it was to act as a "debater's handbook for the convention there," though he claims that this indirect influence would be a "dubious distinction."[23] Probably of greater importance to the Virginia debate, in any case, were George Washington's support for the proposed Constitution and the presence of Madison and Edmund Randolph, the governor, at the convention arguing for ratification.

Another purpose that The Federalist was supposed to serve was as a debater's handbook during the ratification controversy, and indeed advocates for the Constitution in the conventions in New York and Virginia used the essays for precisely that purpose.

An election for President and Commander in Chief of the Military must strive to be above reproach. Our public institutions must give the public confidence that a presidential candidate has complied with the election process that is prescribed by our Constitution and laws. It is only after a presidential candidate satisfies the rules of such a process that he/she can expect members of the public, regardless of their party affiliations, to give him/her the respect that the Office of President so much deserves.

An election for President and Commander in Chief of the Military must strive to be above reproach. Our public institutions must give the public confidence that a presidential candidate has complied with the election process that is prescribed by our Constitution and laws. It is only after a presidential candidate satisfies the rules of such a process that he/she can expect members of the public, regardless of their party affiliations, to give him/her the respect that the Office of President so much deserves.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.